A NONVERBAL LANGUAGE

The high days of Belgian ‘contemporary’ dance are far from over. Old names are still going strong, new names are making fame, and ‘contemporary’ dance is breaking out of its borders. Belgian dance companies are a good argument for banishing the term ‘contemporary’. Isn't it a silly term? Unlike ‘modern’, which projected futures for a range of nowfailed ideologies and left its own archaeology, ‘contemporary’ has no historic potentiality. I admire Belgian choreographers' indifference to the contemporary. Their work has a solemnity that stands out in an increasingly shrill dance world. Belgium is still the place to be. It is a hotbed of dance talent. Performing arts lead us to experience a wide range of sensations. Dancing is one of the most powerful means to strike our feeling for creativity. Classic or contemporary, it’s always delightful coming home after attending an innovative dance perfromance. The elements of movement are space, time and force (or energy). The instrument is the body. The body moves in space and in time with force. The body inscribes the space it moves across, leaving trajectories and choreographic lines and, due to its tangibility, also comes to corporeally fill or occupy a place. It is about understanding the movement of bodies in terms of the physical expression of the performer but also from the perspective of an audience, which serves as a third person perspective on corporeal expression. When watching a body move, the observer becomes attentive to the gestures, rhythm, intentionality, and the crowd of virtual movements that accompany it. Contemporary dance long ago freed itself from the narrative imperative of ballet and works at a level of allusion and ambiguity. Choreographers organise movements in time and in space to create experiences and the audience can start to register its own responses to what it sees.

During an autumn walk I suddenly witnessed the phenomenon called Black Sun. A distant murmuration of starlings rolled "like a drunken fingerprint across the sky," as the poet Richard Wilbur wrote, smudging the dusk horizon with the quickness of a pulsating jellyfish. Many birds flock, of course. But only a relative handful really fly together. The most impressive flockers are arguably those that form large, irregularly shaped masses, such as starling clouds. They often fly at speeds of 40 miles or more per hour, and in a dense group the space between them may be only a bit more than their body length. Yet the entire flock of birds can make astonishingly sharp hairpin turns that appear, to the unaided eye, to be conducted entirely in unison.

Such an epic flock of more than 100,000 birds dancing in the sky is one of the most spectacular natural phenomena in the autumn. In a perfect choreography they perform a true ballet. They swing through the air and increasingly move towards sleeping place. This is perhaps the most beautiful ‘contemporary’ dance performance you can experience. Søren Solkær became specialized in photographing these birds flock and presented them in his book Black Sun. In essence, dance is “the art of movement”, while photography by definition means fixing. It is no coincidence that people sometimes say: “the more difficult to photograph the dance, the better the dance”, or even: “the more beautiful the photos you can take of it, the less movement.” If one dancer dances, it still works. But striving for a certain kind of objectivity in a complex contrapuntal texture — and therefore no flou artistique — is by no means child's play. You see moving architecture and have to pinch for a moment. While dancing is about organizing time and space, photography is about stopping time. The art of photographing dance is to still retain that experience of a passage of time in your fixed image. And because we haven't been able to attend a real live dance performance for a year now due to the corona virus, I was overcome with a kind of nostalgia for a series of fantastic memories on Belgian dance stages.

Black Sun. The flock constantly changes its shape — almost like a phase transition of a substance: From solid to fluid, from matter to ethereal, from reality to dream — where the real time ceases to exist and mythical time pervades | Photo by Søren Solkær.

In the early 1990s, Belgium experienced a boom in contemporary dance. Rosas with Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker and Michèle Anne De Mey, Ultima Vez by Wim Vandekeybus and the performing arts collective Jan Lauwers & Needcompany appeared in every self-respecting theater house. P.A.R.T.S. (Performing Arts Research and Training Studios) was an international contemporary dance training based in Brussels. Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker started P.A.R.T.S. to fill the gap that existed in professional training for contemporary dance. P.A.R.T.S. gained international fame and the world came to Belgium. Among other choreographers and dancers, the American Trisha Brown Company and Merce Cunningham Dance Company were also regular customers on the Belgian stages.

Around the same time, Kunstenfestivaldesarts was created in Brussels and you could see many theater and dance performances at various locations. Since then I have been triggered by moving human bodies and have attended an awful lot of dance performances. It would be a shame to only discuss one specific choreographer and so I will try to describe some specific performances that left a deep impression and set the bar very high.

THE LANGUAGE OF CHAOS | legendary and bruisingly powerful dance work

This choreography balances on the razor-sharp and dangerous dividing line of attraction and repulsion. Once this resulted in a confrontation between two dancers, another time that of two groups, that of the dancers and the music, of the dancers and a compelling play of lines. Aggression, fear and danger blasted through everywhere. The energy was rough and raw, the athleticism fast and frenetic, seeing how the performers act and react, full of the invasion of their personal space. This includes stomping on the stage ground right next to their partner’s prostrate body, demanding twists and turns to deny impact.

In Wim Vandekeybus’ legendary and amazing work, which pushed dance to new physically demanding extremes. Bodies threw themselves one on top of the other, twisted on the floor, threw large plaster bricks toward the skies which their partners narrowly avoid, and risked being crushed by boots kicking hard. They then start throwing stones across the stage full of running bodies, pushing people out-of-the-way and into safety. The male/female relationships were breathless, sexual, violent. It was all fast and controlled to the tiniest detail. It has become known as the work that pushed dance to new physical extremes, introducing a whole new vocabulary of barrelling combat rolls, high flung kicks, and bodies used as missiles.

Simply put, this was a piece with real authenticity, you just can’t fake it, and the result of such discipline and the display of such skill as to be absolutely breath-taking and left me both thrilled and perplexed. This adventurous and wonderful What the Body Does Not Remember has been burnt into my memory like a crazy dream or fantastic phantasm, gone but absolutely not forgotten.

‘What the Body Does Not Remember’ by Wim Vandekeybus | Ultima Vez, 1987. Photos by Danny Willems.

Wim Vandekeybus made this choreography out of high tension and reflex response. He wanted to examine the body in states of extreme pressure. The language he invented was certainly chaotic but there was also a formal logic in his choreography. In one gorgeously adroit quartet, Vandekeybus had his dancers executing folksy little steps while passing around items of clothing at high speed. This serendipitous-looking games of tag or catch was highly patterned.

What the Body Does Not Remember was the fascinating debut performance by Wim Vandekeybus and his company Ultima Vez from 1987. Vandekeybus and composers Thierry De Mey and Peter Vermeersch, who played live on stage with their excellent sextet Maximalist! (This small ensemble would be the template for Ictus Ensemble, which has played under this name since 1994, ed.), received the renowned Bessie Award for for this "brutal confrontation of dance and music: the dangerous, combative landscape of What the Body Does Not Remember." in New York. The serrated intensity of strings, the deep texture of percussion drove on the action like a super-charged engine and added their own shape and lift to the choreography.

‘What the Body Does Not Remember’ by Wim Vandekeybus | Ultima Vez, 1987. Photos by Danny Willems.

Together with Her Body Doesn't Fit Her Soul (1993) — in the presence of two blind performers — and Mountains Made of Barking (Kunstenfestivaldesarts, 1994), these three remain the very best performances in Wim Vandekeybus' repertoire. This, of course, has been viewed from my point of view.

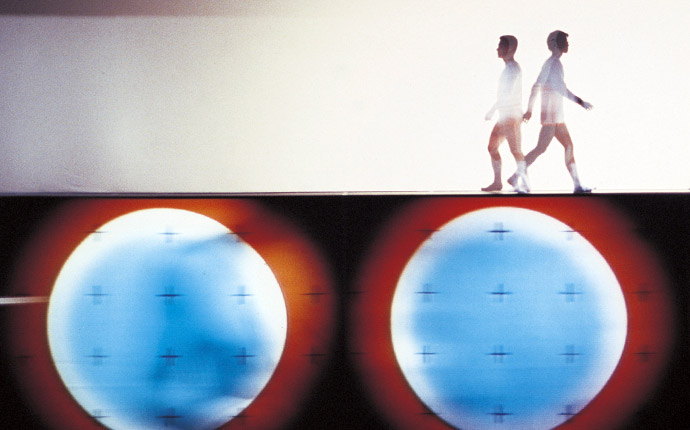

WHEN ACTIONS SPEAK THE LOUDEST | the birth of new media dramaturgy

During the 2nd edition of Kunstenfestivaldesarts in 1995, I witnessed the dance performance S/N by the Japanese collective Dumb Type in Théâtre Varia (Theatre of the French community in Belgium). This is the only dance performance of foreign origin in my short list that I thought should not be missing. It was the very first time I had the feeling that I was watching a multimedia spectacle where all elements were properly and equally implemented.

S/N (Signal/Noise) was a pioneering work in many ways. It was one of the first works to consider the human and political dimensions of HIV/AIDS. Teiji Furuhashi himself, the co-founder of the group, died of an AIDS-related illness in 1995. S/N also used striking visual images, projection screens and immersive sound compositions to explore sexuality and identity politics. Ultimately S/N is seen as a statement about utopian politics and the desire for new human community. On the stage exposed real bodies took the role of noise distorsion fighting against even more sophisticated technological stage devices. With AIDS as the center, issues such a gender, homosexuality, nationality, identity, and life and death were brought out. However they not only criticized the issue of discrimination in contempory society, but they also considered how to use this criticism as an opportunity to form an entirely new love = communication. This communication is rather the different intersections of the multiplicity of the media created by humans (from body language to the computer network) and it must not be transmission devices for power.

‘S/N’ by Dumb Type, 1994, documentation of performance | Photo by Yoko Takatani.

In the early 1980s, a loose-knit collective known as Dumb Type was formed by a group of students at Kyoto City University of Arts to provide a non-verbal (hence “dumb” or “stupid”) response — in the form of installation, performance, music, dance and more — to the onslaught of media imagery and information of contemporary society. Members included visual and video artists, musicians, choreographers and sound engineers. Together, the assembly of multidisciplinary practitioners developed a form of experimental theater that combined performance and multimedia installation in response to Japan’s rapid technological and societal changes of the 1980s and ’90s. The group’s name pivots on the two-fold meaning of 'dumb', asserting both a conceptual and political position. Taking dumb to mean mute, the group sought to remove any trace of intelligible spoken language from their work. Their name was also a rally against the social conservatism and 'dumb' superficiality of Japanese consumer society at the height of the country’s bubble economy.

Dumb Type is known for creating new art forms that portray a dark, cynical and humorous world in which media, consumerism and technology are the norms of everyday life — if not necessarily a welcome one. At the root of Dumb Type’s strongly felt political provocations is an existential dimension — an investigation of what it means to be human within a rapidly changing technological landscape. They are one of the most important groups of artists in Japan that have shown their cutting-edge art works and performances at many museums and art centers internationally. The structure of each collaborative project differs, but the focus on balance between technology and humanity remains the same.

"We were frustrated artists, and wanted to start creating something new with our skills. Most of the time we spent discussing society or whatever, not specific art things. When someone had an idea it would be presented on a piece of paper. If the group was interested, we made it come true. At first the idea would be really open, then gradually it became something very specific. In that way, we're really democratic. Dumb Type is a collaborative group; we don't want a king." — Teiji Furuhashi (1960-1995), one of Dumb Type's founding members

A CHOREOGRAPHER'S SCORE | see the music and hear the dance

Against a black backcloth the five-part piece opened with a deep 'industrial' sound, and then deafening silence. The low-level lighting picked out four female bodies lying on the floor. Behind them were stacked the chairs without which no 1980s contemporary dance work is complete.To the sound of their exhalations, and bodies and hands hitting the floor naturally, the four women moved simultaneously with the precision of machines until one breaks away. They were serious-looking women with civvy haircuts, wearing loose grey tops and skirts and hideous, brown, utilitarian shoes. They executed a series of quotidian gestures. The arrangement changed again, but the synchronisation continued in counterpoint and at a distance, as they rolled over the territory of the stage, sat up, tilted and fell. The four female dancers straightened their T-shirts and clenched their fists. Arms were raised, hands touched hair, rising started and ended with a gentle collapse of limbs. These were the basic movements of Rosas danst Rosas, a choreography by Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker from 1984.

Rosas danst Rosas consisted of four female dancers in rapport with one another and five chapters full of intense physical energy. The drive in this body machine was tempered by a series of ‘very familiar, everyday movements’: the abstraction then changed into a series of small, tactile emotional narratives in which the spectator could recognize himself and by which he was moved. Rosas' first work, Rosas danst Rosas, became a signature piece, giving the company a distinctive female look: full skirts, tomboyish boots, squadron formations. De Keersmaeker and her company revived this piece many times since its creation, but Rosas danst Rosas retains its considerable power to baffle, frustrate and intrigue. I'm looking forward seeing it again one day.

Dancer Laura Bachman at a rehearsal of ‘Rosas danst Rosas’ in Brussels in 2017 | Photo by Anne Van Aerschot.

"Dance is a language, and as in love, the most beautiful things are said through the body. I continue to be obsessed by the art of writing dance as we write music, in time and space." — Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker

Rehearsing ‘Rosas danst Rosas’ in Brussels in 2017 | Photos by Anne Van Aerschot.

In 1983, Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker had her international breakthrough with Rosas danst Rosas, a performance that has since become a benchmark in the history of postmodern dance. Rosas danst Rosas builded on the minimalism initiated in Fase (1982): abstract movements constituted the basis of a layered choreographic structure in which repetition plays the lead role. The fierceness of these movements was countered by small everyday gestures. Rosas danst Rosas is unequivocally feminine. The exhaustion and perseverance that came with it created an emotional tension that contrasted sharply with the rigorous structure of the choreography. The repetitive, “maximalistic” music by Thierry De Mey and Peter Vermeersch was created concurrently with the choreography.

Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker has achieved worldwide success with her concept of “harmonic polarity”. The European standard-bearer for minimal dance, based her work on the musical score, using it as a starting point to explore possible relationships between sound and dance. Her approach is complex, but, perhaps paradoxically, results in a clarity of movement that is both of the postmodern dance movement and uniquely her own.

Composer and movie director Thierry De Mey filmed Rosas danst Rosas in the former technical school of architect Henry Van de Velde in Leuven. The film version is much shorter than the show itself. In his film Thierry De Mey opted for a heavily intercut version in which, apart from the cast of four dancers, he also had all the other performers from the long history of the theatre dance performance along. He made maximum use of the geometrical and spatial qualities of the Van de Veldes building. Incidentally, the building was thoroughly renovated straight after the film was made, making it one of the last testimonials to the original architecture. When the camera settings are completely absorbed in the rhythm and movement of the choreography, the filmed dance performance becomes a new, autonomous work of art. Rosas Danst Rosas is an exciting dance film that has visibly enriched the choreography. The film was shown on all of the major European television channels and also had a cinema career in the art house circuit.

‘Rosas danst Rosas’ by Rosas | A film by Thierry De Mey.

Later on I saw a reprise of Bartók/Mikrokosmos (1987). The musicians' presence on stage (pianists for the first part, a string quartet for the second) marked out the score as the point of departure, from which the dance builded its own microcosms: first a sparring male-female duet, then a skirted and booted girlie-gang, like an elite squad drilled in flouncy mannerisms (Quartuor N°4). Four girls with their boots and black dresses opening like a corole in multiple tumbles, their white panties repeatedly revealed, their hair down and twirling and rushing forward in nervous little gestures. They looked like cheeky, insolent college girls sharing the stage with the musicians. They stamped their feet, pretended to walk on heels, played to seduce the violinists, provoked the public. Shoulder movements, chained turns, tumbles that end with both hands in the hair, heel snapping ... The rigorous clarity was at once dense with suggestion and intellectually very satisfying. I also really enjoyed Drumming (1998) and Rain (2001).

‘Quartuor N°4’ by the Paris Opera Ballet at the Palais Garnier | Music: Béla Bartók, Dancers: Sae Eun Park, Juliette Hilaire, Charlotte Ranson and Laura Bachman | Photo by Agathe Poupeney.

HUIS CLOS | a choreographic enchantment

We entered an empire infinite in nature; a landscape with no bearings, almost abstract. Only texture, light, and matter had rights here. No articulate dialogue: the narration was confined to the image. A succession of scenes that answered each other, merged into each other, and blended in a process of incessant transformation leading to a virtuous cycle: harmony and chaos, chaos and harmony, perpetual movement, and the magical character of the elements. It were the elements that generated the dance.

An ode to nature and its confused opulence unfolded before my eyes. A song in the form of a dance carried by the legendary score of Beethoven's seventh symphony. Snow turned out to be like a fairytale: enchanting and terrifying. Universal and yet each identifying by name. A fable that called into question both our general humanity and our uniqueness. Bodies that sweeped through a landscape and left their mark on it, as well as bodies that swayed and hesitated in response to weather fluctuations. And from this incessant back and forth came choreographic writing.

A tale of snow and dread that revolved around the body, its metamorphoses and its changes of proportions. On the stage transformed into a box where all the strings of burlesque work, it snowed endlessly. It fell almost non-stop, for 75 minutes this choreographic work lasted. This was what fascinated the viewer at first glance: the scenography and the special effects were magical so that the illusion turned out perfectly.

The choreography took on the air of a daydream in the changing tones of a perpetual winter. Neige was a story of burying, mourning and the loss of illusions. It was more than a dance performance, it was a magical, phantasmagic spectacle, a vision of the purest romanticism. The curtain opened to an apocalyptic vision of an avalanche sweeping away everything in its path. Peace returned with the sun breaking through the haze in an aurora borealis effect. But the truce was short-lived, the clouds poured down their snow quickly and in large flakes. The realism was striking. It was through the play with effects that the feeling was created that man was taking place in this universe: the dancers were tossed with manpower in all directions by the gusts of wind. Faced with the raging elements, they seemed lost in this magnificent yet terrifying icy immensity. The dancing perfectly reflected the actions that animated the characters: games, fights and struggles. Sometimes their feelings even shone through, love, fears, joy to walk through this snow, to draw pictures in it ...

The characters operating in this universe were not kind to themselves and the weak were ruthlessly eliminated. We could see with striking realism how a woman was torn to pieces by her mates like wolves fighting over a piece of meat ... And death came into play several times, especially at the end of the choreography. Perhaps that was a bit shocking about this very beautiful dance performance bathed in an atmosphere of beauty.

‘Neige’ by Michèle Anne De Mey | Performed by Gabriella Iacono, Samuel Lefeuvre, Ilse Ghekiere, Kyung Hee Woo, François Brice and Leif Federico Firnhaber. Photo by Michèle Anne De Mey.

Figurehead in the renewal of contemporary dance in Belgium, Michèle Anne De Mey, wanted to create a choreography according to a different methodology. One that started from the data on stage, from a pre-conceived installation with decor and lighting. The dance and the dancers were confronted with this from the beginning.

If Michèle Anne De Mey initially had the idea of staging a fairytale for young and old with nature and the unleashed elements as the main theme, it was her meeting with scenographer Sylvie Olivé — who had appeared on both television and in the cinema — and lighting designer Nicolas Olivier who were the real trigger and the real craftsmen of the show.

Together they spent a year looking for a 'scenographic element' that would determine the performance. In the end they created a snowstorm of paper (for each performance 350 kilos of paper scraps are lifted into the theater tower and snow on the stage for an hour and a half, ed.). They made a 'huis clos' with transparent plastic, a piece of wrapped nature, a dream world of a woman in which different characters wander. One also finds a relationship with the beauty and simply accept it. That dreamy decor took the audience on a contemplative trip, a kind of passage into the unconscious. The dreams had to do with the feeling that you give up, with self-loss. It's about disappearing into the snow, into the mist, into death.

"It was a challenge to bring such a grand, romantic element of nature into a theater, a place where you are normally completely cut off from that nature. It is playing with dimensions in which the bodies disappear. The choreography is not only in the dancers, but also in the scenic dimensions, in the space, in the light, the sound. All these things reinforce each other in a global experience." — Michèle Anne De Mey

‘Neige’ by Michèle Anne De Mey | Performed by Gabriella Iacono, Samuel Lefeuvre, Ilse Ghekiere, Kyung Hee Woo, François Brice and Leif Federico Firnhaber. Photo by Michèle Anne De Mey.

CAN CHOREOGRAPHY BE PERFORMED IN THE FORM OF AN EXHIBITION?

In 2015, Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker brings a continuous dance and music event to the WIELS, center for contemporary art in Brussels. Most of the museum visitors around me stood or seated themselves on the floor, respectfully back, leaving the dance-friendly surface. It’s hard to say if those in attendance found the individual and interrelated performing of seven dancers and seven musicians to be an exhibition. Regardless, it was heartening to note the concentration of the onlookers, in good part because nearly none appeared distracted by their handheld devices except while taking the occasional picture.

Work/Travail/Arbeid is a remake of De Keersmaeker's Vortex Temporum from 2013, a dance of approximately 65 minutes that is inspired by Gérard Grisey's loose and sometimes excited music of the same name. For Work/Travail/Arbeid, the combined performance of Rosas and Ictus has been extended to nine hour cycles, with each hour presenting new combined aspects of Vortex. Even without the title Vortex Temporum, it is likely that those who attended Work/Travail/Arbeid at WIELS gradually felt themselves in the sonic and visually animated vortex of this interconnected display of dancing and music-making. On the gray painted concrete floor, on which the 14 individuals play, differently interconnected and overlapping circles were drawn in chalk. The choreography draws the visitor into its plan as if into a virtual vortex. Its scheme consistently mated one particular dancer with one individual musician. The dance moves grew into athletic spirals and squiggles. The performane expanded dramatically as all the musicians moved their instruments across the floor and between the dancers. Even the piano started to move, pushed on its wheels while the musician continued to play.

"First and foremost, I will remain a dancer. My choreographic practice is still very much influenced by my practice as a dancer. A composer like Bach was also a brilliant performer. The savoir faire, the craft, is very important to me." — Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker

Rehearsal of ‘Work/Travail/Arbeid’ at WIELS | Performed by Marie Goudot. Photo by Anne Van Aerschot.

Finally, the designation of performance or exhibition seems controversial. With the sound of Grisey's catching the attention of WIELS visitors from every vantage point around the atrium, and with Rosas' dancers and their choreography accompanied by the sounds that come in isolated spurts or in mixed combinations, such as deposits of vibrating tones, Work/Travail/Arbeid manages to dramatize the listening.

I sensed from the keen interplay between dancer and musician, and from the viewers’ following the connections, that there was careful listening in the air. It’s not something you can literally see, but in the efforts of Work/Travail/Arbeid, you can feel it all around you.

‘Work/Travail/Arbeid’ at MoMA, New York | Performed by Marie Goudot. Photo by Anne Van Aerschot.

CHAOS REIGNS IN THIS MAGNETIC CHOREOGRAPHY | a natural phenomenon in the theater

An uncanny quietness slowly silences the still murmuring theater hall. A lonely whistle resounds through it. Close your eyes and think of a vast ocean that extends to the far horizon, of the wind as it moves the water, and of the waves rushing to the shore. Then open your eyes again and look at ten very different female dancers in T-shirts and panties of different colors work carefully out of the dark, onto the illuminated rose carpet floor. With a curved torso and hunched shoulders, ten individuals move in slow motion across the stage. First contact occurs when a dancer vaguely points at anothers. From that hint, the individuals slowly form a collective. Inward peace alternates with combativeness. From a deep breath, the group flows up and down like one body. Until one dancer falls out of the group, and the rest molds to the changing pattern. The group moves like animals across the stage, boxing defiantly at the audience and challenging it with tongues sticking out. To disintegrate a little later as a group into an individual, meditative state of being. It seems as if the ten women are lived by Maarten Van Cauwenberghe's soundscape, this time assisted by Elko Blijweert and Bjorn Eriksson, with an all-predominant wind or soft-sounding air conditioning and then again an exciting beat. A thrilling ménage à trois of these acclaimed soundscape artists and an enchanting soundtrack to an enchanting dance performance.

The organic growth of dance and music forms the core of Voetvolk. Because the musician composer is present at all rehearsals, he sees every movement arise and can graft his own work directly onto it. The Sea Within seems to be a logical culmination point of that way of working. The organic is not only at the basis of the performance, the entire choreography breathes and itself moves like an organism.

‘The Sea Within’ by Lisbeth Gruwez, 2018 | Dancer: Chen-Wei Lee. Photo by Danny Willems.

"When we started there was a very obvious link with the intensity of Fabre’s work. It was very energetic and powerful. But along the way we started to develop our own language, in dance and in music. The soundscapes for the Voetvolk performances have become more narrative, but in a subtle way. Technicality is not everything. Details and essence are put up front. The performances are more generous now. The link with the audience is restored. We don’t want to create intellectual choreographies that only a happy few understand; we want to connect with the audience." — Maarten Van Cauwenberghe

Dancer and choreographer Lisbeth Gruwez, together with Maarten Van Cauwenberghe, formed the contemporary dance and performance group Voetvolk. If there’s such a thing as the next generation of contemporary dancers in Flanders, this company would be the perfect example. The two founders have both worked with Jan Fabre, while Gruwez studied at P.AR.T.S. and has danced with Ultima Vez and Needcompany.

The Sea Within is a magnetic show in which Lisbeth Gruwez gives chaos free reign. Her work remains just as sharp and intense as before, but now, rather than zooming in on the individual, the choreographer — who, for the first time, will not be treading the boards herself — has a group of 10 dancers become absorbed in a panoramic, breathing landscape. Together they arrive at a new, contemporary ritual in which the ‘we’ embraces the ‘I’.

"There is a deep masculine side in me, which has been greatly developed by the many male choreographers with whom I have worked. Jan Fabre especially liked to get my wild beast, my Odysseus, out of the closet. But in recent years I have dared to show my feminine side more. I already wear a skirt now." — Lisbeth Gruwez

‘The Sea Within’ by Lisbeth Gruwez, 2018 | Performed by Ariadna Gironès Mata, Cherish Menzo, Daniela Escarleth Romo Pozo, Francesca Chiodi Latini, Giada Castioni, Jennifer Dubreuil Houthemann, Natalia Pieczuro, Sarah Klenes, Sophia Mage & Chen-Wei Lee. Photo by Danny Willems.

The ephemeral nature of dance, the fact that so much disappears from public view, is one of the art form’s frustrations. But, when a work comes back from the past, there’s a unique charm in seeing it with fresh eyes.

Stay amazed!

All images courtesy of the artist. Photos © Søren Solkær, Anne Van Aerschot, Danny Willems, Yoko Takatani, Michèle Anne De Mey and Marie Goudot.

Related stories in Woodland Magazine: