A DEEP, GRITTY-SOUNDING VOICE

A singer recognized for his deep baritone, brooding delivery, and meditative, literate lyrics, Matt Berninger (1971) rose to fame during the 2000s as frontman of Brooklyn indie rockers The National, defined by their somber rock tunes, and his longtime artistic project, EL VY. Matt Berninger is a master of vocal monotony and skillful wordsmith, the man is an enigma who adds his aura of sadness to the crescendoing hymns. But before he found fame in music, Berninger studied at DAAP (University of Cincinnati's College of Design, Architecture, Art and Planning), then put his degree to work as successful Creative Designer, including being involved in New York's dot-com boom.

To be honest, I didn't know Matt Berninger or The National at all until I first heard the song Bloodbuzz Ohio back then in 2010. To my ears Bloodbuzz Ohio sounded like a gorgeous, rich sound that could touch something tender in the coldest of hearts. Upon listening to The National albums that came afterwards, it became clearer than ever that this band deserves nothing less than rock star royalty. The National's music has drawn comparisons to Interpol, the Smiths, Tindersticks, and Tom Waits — the latter due to Berninger's shattered, beautiful earthquake of a voice, which recalls the holy trinity of Cave, Cash and Cohen. However, though concerned with the forensics of heartbreak specifically and the human condition generally, the band isn't mere copycats.

A few years later, when I first heard Return to the Moon on the radio, I had that same feeling again. Perhaps logical because the voice of EL VY is of course the same. And this year is happened again while listening to Serpentine Prison, the first single of his debut solo album. Berninger's voice and melodic sensibility are instantly recognizable. It is a relief to hear 49-year-old Berninger caressing his emotions so gently. For me personally, few people squeeze warmth and sadness through one bundle of vocal cords as effectively as Matt Berninger. Soft piano tones and sleepy guitar sound accompany the American hump through a daily, quite sensitive reverie. We hear a recognizable Berninger who dances on a tightrope between singing and storytelling, and wails about an amorous relationship that seems to have lost the trace of his heyday.

Matt Berninger was an artsy kid. He took art classes in high school; that was his main thing. Berninger loved art, but he was also kind of brainy. When he went to college, he decided he was going to be a doctor. He was in pre-med for one year at Miami University of Ohio but he hated it. Berninger wasn’t bad at it, but he just hated it. The next year, he switched to sculpture. Pre-med to sculpture is a pretty big leap. Then he realized that maybe being a sculptor wasn’t going to be enough. He didn’t love it enough. So he quickly pivoted to graphic design. It was right before graphic design became a household word, where basically anybody with Photoshop could call themselves a graphic designer. Graphic design sounded sexy. It sounded cool. It was somewhere between art and being a professional. He thought it would be mostly about creating posters and record sleeves.

Berninger had to start college over from the beginning and met Scott Devendorf in that first year. Devendorf was also into the graphic arts part of high school and trying to make his own band T-shirts and fun stuff like that. Mainly what attracted him the most was the co-op aspect. They ended up traveling and living together on co-ops at graphic design firms and together with former classmates they pursued music, first with garage punk band Nancy (named after Berninger’s mom). Berninger had never been in a band before and didn’t play an instrument, but he had his own extraordinary skills and aptitudes, so he became a singer. Nancy released the album Ruther 3429 — a nod to the address where Berninger once lived as a student — before disbanding when members including Berninger and Devendorf relocated to Brooklyn, New York. While Nancy was mainly a fun creative outlet at the time, the experience helped prepare Berninger as a performer.

The two former graphic design students gravitated to New York for internships and jobs, embarking on a career in advertising. And they did well. They got jobs at places that were just starting to do websites and new media. It was at the beginning of that. They got jobs that were kind of well-paying for just out of college. Then, just because they were well-paying, and no one else was doing it, they rose in the ranks. Berninger felt professionally motivated and excited. He felt like, "Wow. I can be a grown up man in the world, pay my own rent, and buy my own TV."

"That was right before graphic design was sort of a household term. It was before Photoshop and Illustrator. I remember when I heard the term graphic designer back in ’91, I didn’t know what that was. It sounded cool. I thought it would be mostly posters and record covers." — Matt Berninger

Scott Devendorf was hired by a small design firm doing print materials for art books and catalogues for museums like the Guggenheim. During the dot.com boom of the late 1990s, Berninger joined one of the first digital media agencies at the time called Nicholson NY. He was a part of the first graduating class that learned how to use HTML and create interactive graphic designs. He redesigned websites and created campaigns for companies and products ranging from the Metropolitan Museum of Art to engineering parts to Viagra. Berninger rose through the ranks quickly, working his way up from Graphic Designer to Creative Director in a handful of years. His timing was great — he got in on the ground level of the dot-com boom and was making good money. He also had crazy stock options. On paper, Berninger was worth a million dollars before he turned 30. That was insane. He was happy to have a nice paycheck and spend the money buying records, going to shows at the Mercury Lounge, eating out every day, and drinking in bars. He lived in a huge unconverted loft in Brooklyn and threw massive parties and hosted art-gallery shows.

Then it all came crashing down. The Internet bubble popped, and Berninger spent a year and a half at his job laying off all the junior designers he’d become friends with. It was awful. All his stock-option money disappeared. He’d convinced his parents to invest in the company, so he even managed to lose them money. All the things he enjoyed about his job were gone, so eventually he laid off himself in 2003. He continued to freelance here and there for several years, but the idea of working hard for a client that he didn't really respect got to him, and he couldn't do it anymore. Berninger decided to try one last time to make his hobby his profession. Quitting the dot-com world to start a band taught him about the power of good karma and creative freedom — even at the cost of a little cash.

Looking back, there was something about the DIY quality of those early web-design days that made him realize there was no script to life. In a way, it was very punk rock and a completely new art form. He thinks it was that sense that it’s okay to make it up as you go along that gave him the confidence to just start a band. He hadn’t played music for years, but he didn’t worry about whether he was qualified or not. After all, the Sex Pistols weren’t necessarily great musicians, but they did reinvent the idea of a band.

"I became a lover of music at UC. Being around all these creative people, drinking coffee and listening to rock music while we worked on design projects all night long — that was where I really dove in and started studying musicians and obsessing about the writing. It was a formative experience in terms of friendships, music and art." — Matt Berninger

Matt Berninger formed a new band in Brooklyn with his friends from college: Devendorf (bass) and his brother Bryan (drums) and Aaron Dessner (guitar, keyboards). They grew up around one another outside Cincinnati. The four formed The National in 1999, making music after work, gigging around the city and developing their sound. They started making music really slowly. When they began practicing one or two days a week, their rehearsal space was literally right next door to Interpol’s. Interpol sounded so damn cool. At that time, The National had no idea how to make music together, and then they heard these guys in the other room who knew exactly what they wanted to sound like and exactly what they wanted to look like. It was motivating. "They were cool as shit; we were just figuring out how to be a band", Berninger recalled. Interpol literally did a photoshoot in the hallway and they had to walk through to get to their rehearsal room. That was happening right next door to them, so why couldn’t it happen in their room, too? Proximity to other people having crazy, reckless, delusional pipe dreams is one of the most motivating things. It took The National a few years to get anywhere close to the world that Interpol were in.

"The National started in the middle of that," Berninger recalled. "If I had to, I could go back to a job. If I had to, I know how to do an interview. I know how to get a job. If this band fails, I can always go back and be a creative director or do lots of different things because I’m good at getting jobs. I’m good at ingratiating myself and making myself appear useful. I knew I could have a job — maybe that’s what it was — it wasn’t the job itself. I figured out I can come back if this rock and roll delusion turns out to be a delusion."

The quartet secured a weekly residency at Manhattan’s Luna Lounge and went to work on their debut album. The National saw release in 2001 on Brassland Records, an independent label founded by Aaron Dessner and his twin brother Bryce, a Yale graduate with a master’s degree in music. Bryce Dessner soon joined the group on guitar, solidifying a lineup that would remain intact through their rise to mainstream success.

They had a healthy self-deprecating humor… they never let themselves believe they were bigger than they were. They were constantly knocking each other down ego-wise. But then when they needed it, they would inflate each other. The fact that it was happening slower maybe allowed them to have the time and perspective an extra night’s sleep to wake up and go, "All right, I’m not walking away yet." They were smart enough to be careful and protect their ability to make the type of stuff the way that they wanted to make it. Patience… and respect that it took time. Make sure to give yourself that time. Also respect the failure. Respect every time you play the show when nobody is there. Learn how to be better. Respect that terrible, really bad review. Never agree with them, but respect them.

From left: Bryce Dessner, Pauline de Lassus, Carin Besser and Berninger. The band members’ wives played a large role on the National’s new album. © Aaron Richter for the New York Times

"We even talk in terms of colors when we’re working on songs. When a song’s too blue, it needs a little yellow. I’m the lyricist and singer, and that part is like the typography inside our work. The drums are the grid." — Matt Berninger

It's not to say their design work has ended. If Berninger and Devendorf went into graphic design to design band T-shirts, posters and record covers, they’ve certainly met that humble goal — only now it’s for their own band. They’ve had a hand in all their record album designs, and Devendorf points out the many visual aspects to music, including live shows, posters, merchandise and music videos. Berninger explains that making music is similar to creating visual art or graphic design or any type of composition because it all comes down to communicating some message. "The more you work on something and hone in on it, you go back and tear it apart and put it back together," says Berninger. "It’s the process of refinement. I know that UC and that design program definitely instilled that in me."

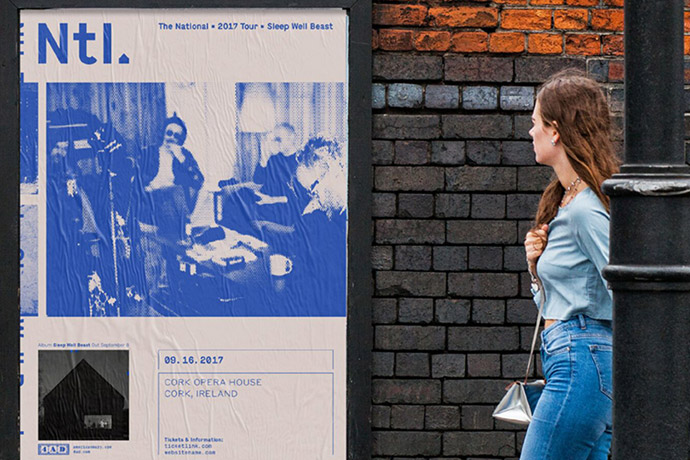

New York-based Pentagram — Scott Devendorf worked at its New York office from the late 1990s until the early 2000s — has collaborated with The National on designs for their record Sleep Well Beast, working across the sleeve design and promotional materials ranging from T-shirts to more unexpected items, like staplers and sellotape dispensers. According to Pentagram, The National "were amused by the appearance of hiring a large, grown-up branding agency to do their campaign. So there’s a bit of irony in the idea of an indie band having a full-on corporate identity, even going so far as to produce a corporate standards manual." It’s a cheeky, wry and slightly punkish gesture that feels more befitting to a post punk band, or something from the Factory Records stable; a departure from The National’s usual more sensitive rock stylings.

So one thing led to another, and the guys from The National found it quite amusing to push the idea of making it corporate. The designs were based around a five-sided house-like shape, inspired by the barn built by the band in Hudson, New York, where the album was recorded. The agency created a corporate Ntl. logotype used across all brand merchandise.

In 2005, The National graduated from Brassland and signed to the considerably larger British label, Beggars Banquet, releasing a series of critically acclaimed albums — Alligator (2005), Boxer (2007), High Violet (2010) and Trouble Will Find Me (2013) — and touring relentlessly, mostly throughout North America, the UK, Europe and Australia, though also in such far reaching locales as Japan, Turkey, and Moscow. They'd grown in popularity to become one of the most beloved and well-known bands on the independent music circuit.

Ivo Watts-Russell and Peter Kent, employees of the Beggars Banquet record store and label, founded Axis Records in late 1979 as a property of Beggars Banquet that was run by the two. After the first four Axis singles in early 1980, the name was changed when it became apparent that the name Axis was already being used by another music company. The solution to this problem came from a promotional flyer that they had printed to call attention to the new releases. The flyer's designer had added some typography that played on both the new year and the idea of progress: 1980 FORWARD, 1980 FWD, 1984 AD, 4AD. Scrambling for a new name, Ivo glanced at the flyer and suggested 4AD. Peter Kent agreed, and, with that split-second decision, 4AD was named.

It took time for Matt Berninger to come out of his shell. His early days fronting The National were littered with awkward gigs at which the gawky young singer would down red wine for his nerves, keep his back to the crowd and struggle to hit the high notes. But starting with 2005’s Alligator, one critically acclaimed record followed another and a new man emerged. By 2013’s Trouble Will Find Me, Berninger, with his hip beard and specs, had become one of the most charismatic frontmen on the planet. It’s this cultivated rock star persona and its laughable improbability that Berninger examined in his new collaboration with crafty multi-instrumentalist Brent Knopf of Portland's own Ramona Falls and Menomena, EL VY ("pronounced like a plural of Elvis", apparently).

Through startling self-awareness, surreal wit and a knack for bringing the listener in on the joke, he basically positioned himself as the stand-up comedian of indie rock frontmen. EL VY created an enthralling musical space where Matt Berninger could explore the idea of being Matt Berninger. Working in his free time in hotels, on tour buses, even in a tent in his backyard, Berninger developed melodies and lyrics off these musical sketches. He sended his efforts to Knopf and he'd send him something back that was completely reinvented and had all kind of new ideas. This kind of remote back-and-forth was hardly anything new for the longtime friends, who had sifted through years' worth of material emailed between one another. It was in the fall of 2014 that Berninger and Knopf started turning the casual collaboration into a more focused endeavor to finally deliver Return to the Moon, their debut album as EL VY. The great strength of El Vy, by contrast, is that it brings forth both members’ strengths to create something that sounds like a proper polished debut. Knopf created a landscape on which the strange imagination of Berninger paints.

Frontmen are often bigger than their voices, and Berninger, a headstrong, charming former Creative Director who vibrates with ideas and similes, is a confessed egotist. But on a new album of The National, I Am Easy to Find (2019), and a 26-minute black-and-white film with the same name soundtracked by the group, the five bring in other musicians, to see how much Berninger they can remove and still be The National. The shift was prodded by two non-musician collaborators: the American film and music video director, writer and graphic designer Mike Mills, and Berninger’s goodlooking wife, Carin Besser (writer, editor, lyricist and film producer).

And finally, Serpentine Prison is an album that you listen to on a rainy lockdown day, to take in the drizzle of the songs indoors and warm you up in a certain way. Intimacy is one of the keywords that sums up the record well. A hopelessly romantic soul shouts out its melancholy in a very modest and elegant way, and does so with masterful musical accompaniment (with Gail Ann Dorsey, Bowie’s bassist, and producer Booker T Jones). The man's first solo album takes you from start to finish, and as a listener you don't have to do much for it. As with The National, Matt Berninger’s brilliantly obtuse way with words swirls into frame frequently.

Stay amazed!

All images courtesy of the artist.

Header photo © Graham MacIndoe / Photo of EL VY with Brent Knopf © Zlatko Batistich

See/read also some story related movies/interviews:

Related stories in Woodland Magazine: