HIGHWAY CODE

Rosalie Gascoigne (1917-1999) — a highly regarded New Zealand-born Australian sculptor and assemblage artist — is best known for her distinctive and poetic assemblages of mostly found materials: wood, iron, wire, feathers, and yellow and orange retro-reflective road signs. Gascoigne brought these items from everyday life into new frames of reference, often finding beauty in overlooked things that had been discarded and left to weather. Gascoigne’s abstractions move between metaphor and analogy, topography and geography, not only informed by an ‘ideology of nature’ but reveal the structuring logic of minimalism.

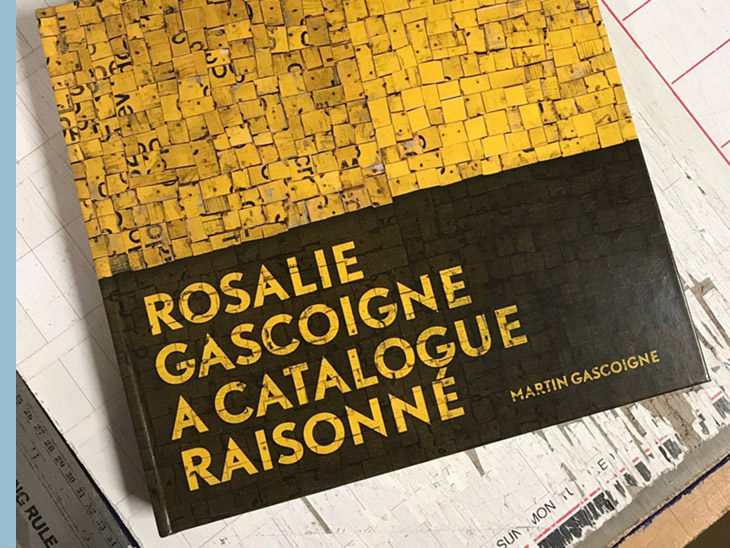

In 1974, at the age of 57, she had her first exhibition. Behind this late coming-out lay a long and unusual preparation in looking at nature for its aesthetic qualities and collecting found objects. Her highly successful first solo exhibition was followed by an exceptionally rapid rise to recognition as one of Australia’s most celebrated contemporary artists. Her son, Martin Gascoigne, has written a book cataloguing his mother's complete body of artwork; Rosalie Gascoigne: A catalogue raisonné.

In 2010, I accidentally came across this Australian artist whilst researching ideas for a course on typography in the form of a timeline. I didn't know who she was but I immediately loved her colorful assemblages made of a collection of Schweppes boxes and retro-reflective road signs on wood which she cut up and rearranged to form poetic compositions based around the grid often incorporating typography. I wondered about the cut up yellow retro-reflective road signs she had reworked into fragmented and incomprehensible art pieces.

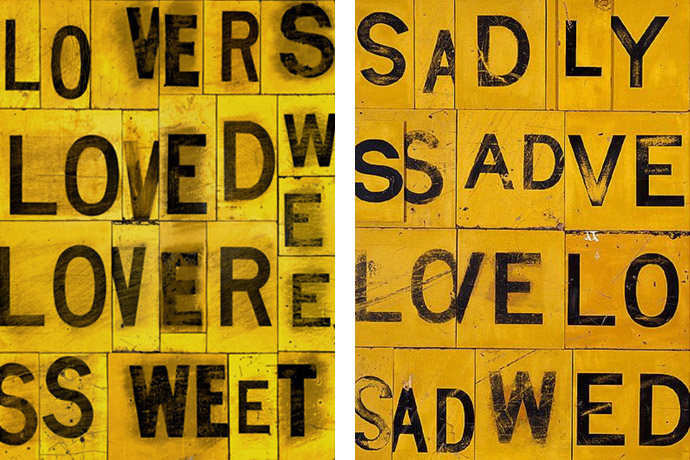

Sweet Lovers, 1990. Sawn plywood retroreflective road signs, on plywood backing. The title comes from a song by William Shakespeare in As you like it, act 5, scene 3, the last two lines of the refrain reading: “When birds do sing, hey ding a ding, ding; Sweet lovers love the spring.” | Sweet Sorrow, 1990. Sawn plywood retroreflective road signs, on plywood backing. The title comes from William Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet, act 2, scene 2: JULIET. “Good night, good night! parting is such sweet sorrow, That I shall say — good night, till it be morrow.”

Rosalie Gascoigne's haunting visual depictions of the Australian landscape have rapidly propelled her into the spotlight of international fame. Yet until she was well into her fifties she was completely unknown as an artist. My readings about her traces the experiences that shaped this complex and fascinating woman, from her difficult childhood in New Zealand to the heady acclaim that greeted her work when it finally came to the attention of those capable of recognising its special quality. The space and freedom she saw in the country around her provided not only a great contrast to the restrictions of her life in Auckland but also an escape from the tedious domesticity of life as a 1950s housewife in a very isolated environment. Her interest in making art from the materials she found around her grew out of a deep desire to surround herself with beauty. Later and almost by chance, she was 'discovered' and was able to develop her work to the point where it is now greatly sought after by international art connoisseurs.

Gascoigne covered the backyard of their family homes with interesting pieces of wood, tree stumps and other things she found. Gascoigne's work is made from assembled found objects with a deep connection to place. Retroreflective road signs, old soft drink boxes, wood — Gascoigne found these materials to create artworks. Driven by process, she would discard “a proper nothing”, choosing to rework, reassemble and continually collect. Her eye was drawn to the colour and shape of the environment around her.

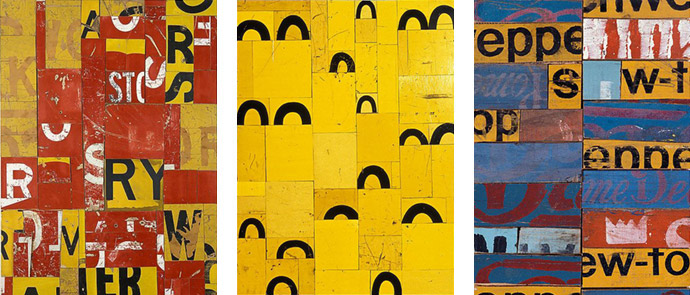

Gentlemen of Japan, 1995. Sawn plywood road signs, some retroreflective, on composition board. “I had some red pieces of reflective material, and I’d just been at the Japanese kite-flying festival, and that read to me as the gentlemen of the Mikado.” | Birdsong, 1999. | Regimental Colours A, 1990–91.

"I don’t want it to be dramatically lit, but I do want it to sometimes flash at you, as road signs do, and then go sullen, then flash, like a living thing." — Rosalie Gascoigne

The book written by Martin Gascoigne, who had a close relationship with his mother on matters of art, brings together the 692 known works she produced between 1966 and her death in 1999. If you want to know more about how the book came into life, read the interview with Martin Gascoigne..

Gascoigne is a much-lauded and much-copied australian artist. A remarkable career for a woman who thought she was not able to be an artist because she couldn't draw and couldn't paint. I would describe her collages as a sort of fragmented, scattered visual poetry.

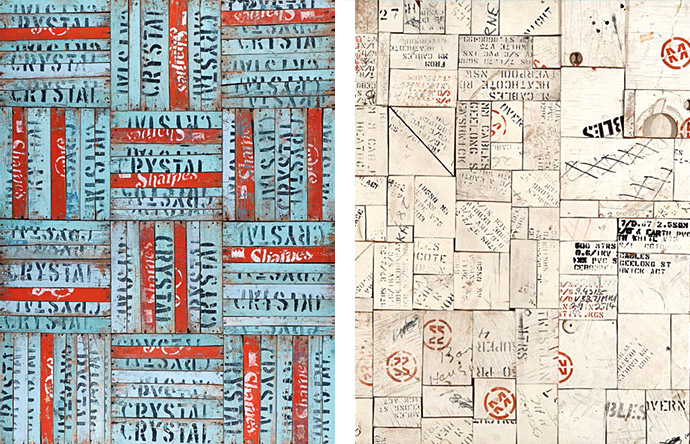

The Marriage Feast, 1988–89. Painted, stencilled sawn and split wood from soft-drink boxes, on plywood backing.

Club Colours, 1983. Painted and stencilled wood from soft-drink boxes, on plywood. “It is rather fun thinking of names that fit and in the end I called that ‘Club Colours’. I kept seeing football socks and things.” | Milky Way, 1995. Sawn painted and stencilled plywood from cable reels with ink markings, on composition board.

All images courtesy of the artist.